Brain lobes‚ crucial for diverse functions – from movement and sensation to memory and language – represent distinct regions within the cerebral cortex․

Understanding these lobes‚ like the frontal‚ parietal‚ temporal‚ and occipital‚ is fundamental to comprehending neurological processes and potential disorders․

What are Brain Lobes?

Brain lobes are distinct‚ specialized regions of the cerebral cortex‚ the outermost layer of the brain responsible for higher-level cognitive functions․ These lobes – frontal‚ parietal‚ temporal‚ and occipital – aren’t rigidly separated but rather work in a highly interconnected manner․ Each lobe manages specific functions‚ contributing to our overall ability to perceive‚ think‚ and act․

The parietal lobe‚ for instance‚ controls sensation‚ while the occipital lobe processes visual information․ The temporal lobe is vital for auditory processing and memory‚ and the frontal lobe governs executive functions like decision-making and motor control․ Understanding these divisions is key to appreciating the brain’s complex organization and functionality․

Historical Overview of Brain Lobe Research

Early explorations into brain function‚ dating back to phrenology in the 19th century‚ attempted to link personality traits to specific skull locations – a precursor to lobe-based understanding․ However‚ significant progress emerged from clinical observations of patients with localized brain damage․ Cases like Phineas Gage in 1848 highlighted the frontal lobe’s role in personality and behavior․

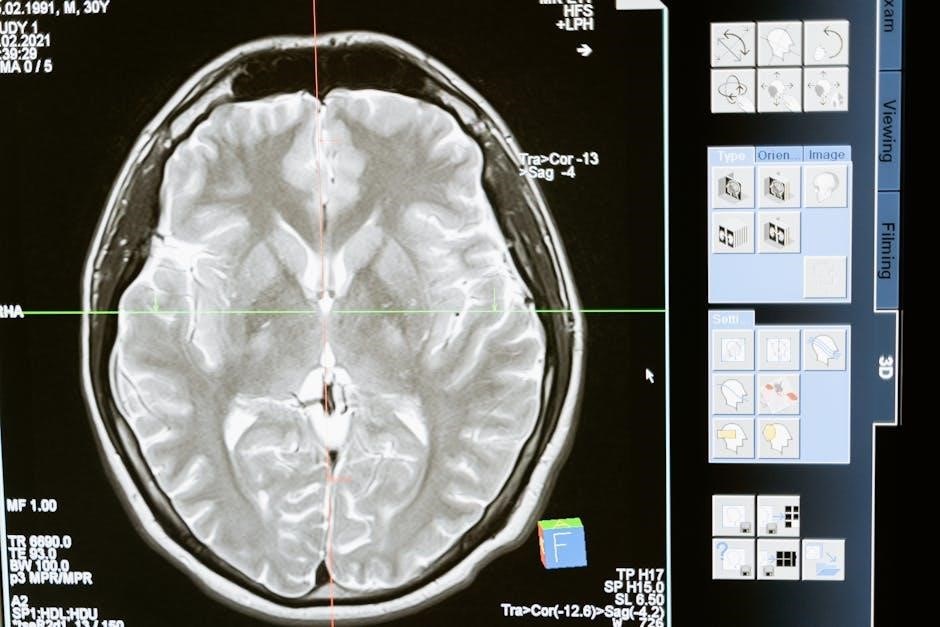

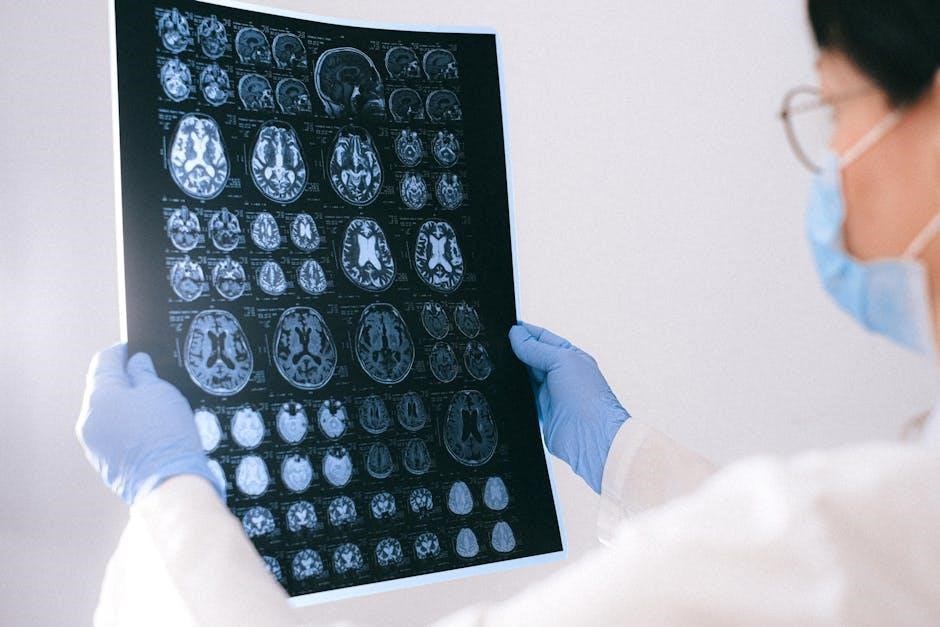

Paul Broca’s and Carl Wernicke’s work in the late 1800s established crucial links between specific lobe areas and language abilities․ Later‚ advancements in neuroimaging techniques‚ like fMRI and PET scans‚ allowed researchers to non-invasively study lobe activity during various tasks‚ refining our knowledge of their intricate functions․

The Frontal Lobe

The frontal lobe‚ the brain’s largest‚ governs executive functions‚ motor control‚ and speech; it’s vital for planning‚ decision-making‚ and voluntary movement․

Location and Key Features

The frontal lobe occupies the anterior portion of the cranial cavity‚ extending from the forehead back to the central sulcus‚ a prominent groove separating it from the parietal lobe․ It’s characterized by a large size and a highly convoluted surface‚ featuring gyri (ridges) and sulci (grooves) that increase its surface area․

Key features include the prefrontal cortex‚ responsible for higher-level cognitive functions‚ and the motor cortex‚ controlling voluntary movements․ Broca’s area‚ crucial for speech production‚ is typically located in the left frontal lobe․ The frontal lobe’s anterior location makes it particularly vulnerable to injury‚ potentially leading to significant functional impairments; Its development continues well into adulthood‚ influencing personality and decision-making abilities․

Functions of the Frontal Lobe

The frontal lobe orchestrates a vast array of complex cognitive processes․ Executive functions‚ including planning‚ problem-solving‚ and impulse control‚ reside here‚ enabling goal-directed behavior and decision-making․ It’s central to personality expression and emotional regulation․

Motor control‚ specifically initiating and coordinating voluntary movement‚ is governed by the motor cortex within the frontal lobe․ Speech production relies heavily on Broca’s area‚ typically located in the left hemisphere‚ facilitating the formation of articulate language․ Damage to this area can result in expressive aphasia․ The frontal lobe integrates information from other brain regions‚ allowing for nuanced responses to environmental stimuli and complex social interactions․

Executive Functions & Decision Making

Executive functions‚ largely attributed to the prefrontal cortex within the frontal lobe‚ encompass higher-level cognitive skills vital for daily life․ These include planning‚ working memory‚ cognitive flexibility‚ and inhibitory control – the ability to suppress impulsive reactions․

Decision-making processes are intricately linked to these functions‚ involving weighing potential outcomes‚ assessing risks‚ and selecting appropriate courses of action․ The frontal lobe integrates emotional input with rational thought‚ influencing choices․ Deficits in executive function can manifest as difficulty organizing tasks‚ poor judgment‚ and impaired problem-solving abilities‚ significantly impacting an individual’s capacity to navigate complex situations effectively․

Motor Control & Voluntary Movement

The frontal lobe‚ specifically the primary motor cortex located within‚ plays a pivotal role in motor control and initiating voluntary movement․ This region contains a topographical map of the body‚ where specific areas correspond to controlling movements in different body parts․

Signals originating in the motor cortex travel down the spinal cord‚ activating muscles to execute intended actions․ Beyond initiation‚ the frontal lobe also contributes to planning and sequencing complex movements․ Damage to this area can result in paralysis or weakness on the opposite side of the body‚ highlighting its critical function in coordinating physical activity and enabling purposeful motion․

Speech Production (Broca’s Area)

Located in the frontal lobe‚ typically on the left hemisphere‚ Broca’s area is fundamentally involved in the physical production of speech․ It governs the motor commands necessary to articulate words‚ coordinating the muscles of the mouth‚ tongue‚ and vocal cords․

While comprehension isn’t its primary function‚ Broca’s area is crucial for forming grammatically correct sentences․ Damage to this region often results in Broca’s aphasia‚ characterized by labored‚ fragmented speech‚ where individuals struggle to express themselves fluently‚ despite understanding language․ This highlights its essential role in translating thought into spoken words and enabling effective communication․

The Parietal Lobe

The parietal lobe integrates sensory information‚ including touch‚ temperature‚ and pain‚ and plays a vital role in spatial awareness and navigation․

Positioned behind the frontal lobe and above the temporal lobe‚ the parietal lobe occupies a significant portion of the cerebral cortex․ Its boundaries are clearly defined by the central sulcus‚ separating it from the frontal lobe‚ and the parieto-occipital sulcus‚ distinguishing it from the occipital lobe․

Key features include the primary somatosensory cortex‚ responsible for processing tactile sensations‚ and the superior and inferior parietal lobules‚ involved in spatial orientation and integration of sensory information․ The postcentral gyrus‚ housing the somatosensory cortex‚ allows for precise localization of touch‚ pressure‚ and pain․ This lobe demonstrates considerable interhemispheric variation‚ contributing to specialized functions in each hemisphere․ Its structural complexity supports a wide range of cognitive processes․

Functions of the Parietal Lobe

The parietal lobe orchestrates a multitude of crucial functions‚ primarily centered around sensory perception and spatial awareness․ It receives and processes sensory input‚ including touch‚ temperature‚ pain‚ and pressure‚ via the primary somatosensory cortex․ This allows for detailed interpretation of bodily sensations and environmental stimuli․

Furthermore‚ the parietal lobe plays a vital role in spatial orientation‚ navigation‚ and understanding the body’s position in space․ It’s also implicated in processing numerical information and performing mathematical calculations․ Damage to this lobe can result in difficulties with spatial reasoning‚ neglecting one side of the body‚ or impairments in sensory integration‚ profoundly impacting daily life․

Sensory Perception (Touch‚ Temperature‚ Pain)

Within the parietal lobe resides the primary somatosensory cortex‚ the brain’s central hub for processing tactile information․ This region meticulously receives signals regarding touch‚ pressure‚ temperature‚ and pain from throughout the body․ Specialized receptors transmit these sensations via neural pathways‚ allowing for conscious awareness and appropriate responses․

The intensity and location of these stimuli are precisely mapped within the somatosensory cortex‚ enabling accurate perception․ This intricate system is fundamental for interacting with the environment‚ protecting against harm‚ and experiencing the world through physical sensation․ Disruptions can lead to diminished or altered sensory experiences․

Spatial Awareness & Navigation

The parietal lobe plays a critical role in constructing and maintaining our internal representation of space․ This allows us to understand our body’s position relative to the surrounding environment‚ and to navigate effectively․ Complex calculations involving visual‚ auditory‚ and proprioceptive information converge within the parietal lobe to create a cohesive spatial map․

This ability is essential for everyday tasks like reaching for objects‚ avoiding obstacles‚ and remembering locations․ Damage to this area can result in difficulties with spatial orientation‚ judging distances‚ and even recognizing familiar places‚ impacting independent functioning and daily life․

Processing Numerical Information

Surprisingly‚ the parietal lobe isn’t just about spatial reasoning; it’s also deeply involved in processing numerical information․ Specifically‚ areas within the intraparietal sulcus are activated during mathematical calculations and quantity estimation․ This includes tasks like comparing numbers‚ performing arithmetic‚ and understanding numerical magnitude․

Research suggests a “number line” representation exists within the parietal lobe‚ where numbers are mentally arranged in a spatial order․ Damage to this region can lead to difficulties with basic arithmetic‚ number comprehension‚ and even recognizing the correct quantity of items․ This highlights the parietal lobe’s crucial role in cognitive functions beyond simple sensation․

The Temporal Lobe

Temporal lobes are vital for auditory processing‚ memory formation—particularly via the hippocampus—and language comprehension‚ housed within Wernicke’s area․

The frontal lobe‚ the largest of the brain’s lobes‚ is prominently positioned at the very front of the skull‚ extending from the forehead back to the central sulcus․ Its defining characteristic is a gradual narrowing towards the anterior portion․ Key features include prominent gyri (ridges) and sulci (grooves)‚ increasing its surface area for complex processing․

Within the frontal lobe resides the prefrontal cortex‚ responsible for higher-level cognitive functions․ The precentral gyrus‚ a crucial landmark‚ houses the primary motor cortex․ This lobe demonstrates significant developmental changes‚ maturing later than other brain regions‚ and is particularly vulnerable to injury․ Its location makes it susceptible to damage from penetrating injuries․

Functions of the Temporal Lobe

The temporal lobe‚ situated beneath the parietal lobe and flanking the ears‚ plays a pivotal role in auditory processing and memory formation․ It’s responsible for deciphering sounds‚ enabling us to recognize speech and music․ Crucially‚ it houses the hippocampus‚ essential for forming long-term memories and spatial navigation․

Furthermore‚ the temporal lobe contains Wernicke’s area‚ vital for language comprehension․ Damage to this area can result in difficulty understanding spoken or written language․ It also contributes to visual processing‚ particularly recognizing objects and faces․ The amygdala‚ involved in emotional responses‚ resides within the temporal lobe‚ linking emotions to memories․

Auditory Processing & Hearing

Within the temporal lobe resides the primary auditory cortex‚ the brain’s central hub for processing sound information․ This region receives signals from the ears‚ interpreting frequencies and amplitudes to create our perception of hearing․ It’s not merely about detecting sound; the auditory cortex analyzes complex auditory scenes‚ distinguishing between different sounds and identifying their sources․

This intricate process allows us to understand speech‚ appreciate music‚ and navigate our environment using auditory cues․ Specialized areas within the auditory cortex process specific aspects of sound‚ like pitch and timbre․ Damage to this region can lead to various hearing impairments‚ ranging from difficulty understanding speech to complete deafness․

Memory Formation (Hippocampus)

Deep within the temporal lobe lies the hippocampus‚ a critical structure for forming new long-term memories․ It doesn’t store memories itself‚ but acts as a crucial intermediary‚ consolidating information from short-term to long-term storage elsewhere in the brain․ This process involves strengthening connections between neurons‚ creating lasting memory traces․

The hippocampus is particularly important for spatial memory – our ability to remember locations and navigate environments․ Damage to the hippocampus can result in profound amnesia‚ the inability to form new memories․ It plays a vital role in declarative memory‚ encompassing facts and events‚ impacting our personal history and knowledge base․

Language Comprehension (Wernicke’s Area)

Located within the temporal lobe‚ typically on the left hemisphere‚ Wernicke’s area is paramount for understanding spoken and written language․ It enables us to decipher the meaning of words and construct coherent sentences‚ allowing for effective communication․ Damage to this area results in Wernicke’s aphasia‚ characterized by fluent but nonsensical speech – individuals can produce words easily‚ but their meaning is often garbled or irrelevant․

Individuals with Wernicke’s aphasia also struggle to comprehend language‚ often failing to understand what others are saying․ This area works in concert with Broca’s area (in the frontal lobe) to facilitate both language production and comprehension‚ forming a crucial neural network for linguistic processing․

The Occipital Lobe

Located at the back of the brain‚ the occipital lobe is dedicated to visual processing‚ interpreting shapes‚ colors‚ and motion from our eyes․

The frontal lobe‚ the largest of the brain’s lobes‚ is situated at the very front of the skull‚ extending from the forehead back to the central sulcus․ Its defining characteristic is a significant increase in size compared to other lobes‚ particularly in humans․ Key features include prominent gyri (ridges) and sulci (grooves)‚ increasing its surface area for complex processing․

A crucial landmark is the prefrontal cortex‚ responsible for higher-level cognitive functions․ Beneath the surface lies gray matter‚ densely packed with neuronal cell bodies‚ and white matter‚ facilitating communication between different brain regions․ The frontal lobe’s anterior position makes it vulnerable to injury‚ potentially impacting personality and executive functions․

Functions of the Occipital Lobe

The occipital lobe‚ located at the back of the brain‚ is primarily dedicated to visual processing․ It receives information directly from the eyes and interprets it‚ enabling us to perceive the world around us․ Key functions include analyzing shape‚ color‚ and motion․ Within the occipital lobe‚ specialized areas handle different aspects of vision․

Color recognition relies on specific regions‚ while others detect movement․ Damage to this lobe can result in various visual impairments‚ including blindness or difficulty recognizing objects․ It’s crucial for spatial awareness and depth perception‚ contributing significantly to our interaction with the environment․ The occipital lobe works in concert with other lobes to create a complete visual experience․

Visual Processing & Interpretation

Visual processing within the occipital lobe isn’t simply about ‘seeing’; it’s a complex process of interpretation․ The primary visual cortex receives raw data from the eyes‚ breaking down information into components like lines‚ edges‚ and colors․ Subsequent areas then integrate these elements to form recognizable objects and scenes․ This hierarchical processing allows for increasingly sophisticated interpretation․

The lobe distinguishes between different forms‚ assesses depth‚ and tracks movement․ This intricate system enables us to navigate our surroundings and interact with the visual world effectively․ Disruptions can lead to agnosia – the inability to recognize objects – or other visual deficits‚ highlighting the occipital lobe’s critical role․

Color Recognition

Color recognition‚ a seemingly simple perception‚ relies on specialized areas within the occipital lobe․ While initial visual processing identifies wavelengths of light‚ assigning meaning – ‘red‚’ ‘blue‚’ ‘green’ – occurs through complex neural pathways․ These pathways involve interactions between the visual cortex and other brain regions‚ enabling us to perceive a vibrant spectrum․

Damage to specific areas can result in achromatopsia‚ a condition characterized by color blindness despite normal visual acuity․ This demonstrates that color perception isn’t merely a function of the eyes‚ but a sophisticated cognitive process orchestrated by the brain․ The occipital lobe ensures consistent recognition‚ vital for object identification and environmental navigation․

Motion Detection

Motion detection‚ essential for interacting with a dynamic world‚ is primarily processed within the occipital lobe‚ specifically in areas like V5 (also known as MT)․ This region analyzes visual input for changes in position and velocity‚ allowing us to perceive movement․ It’s not simply registering light changes; it’s interpreting those changes as indicative of an object’s trajectory․

This capability is crucial for tasks like catching a ball‚ avoiding obstacles‚ and even understanding the intentions of others․ Damage to V5 can lead to akinetopsia‚ a rare condition where individuals cannot perceive motion‚ seeing the world as a series of still frames․ The occipital lobe’s role in motion detection highlights its importance in spatial awareness and survival․

Interconnectedness of the Lobes

Brain lobes don’t operate in isolation; they communicate via complex pathways․ Integrated processing allows for higher-level cognitive functions and coordinated responses․

Communication Pathways

Brain lobes are intricately connected through vast networks of white matter tracts‚ serving as crucial communication highways․ These pathways‚ including the corpus callosum and association fibers‚ facilitate rapid information transfer between hemispheres and lobes․

The arcuate fasciculus‚ for instance‚ connects the temporal and frontal lobes‚ vital for language processing․ Sensory information travels from the parietal lobe to the frontal lobe for integration and response planning․

These pathways aren’t simply conduits; they’re dynamic‚ capable of strengthening or weakening based on experience‚ a principle known as neuroplasticity․ Disruptions to these pathways‚ due to injury or disease‚ can lead to significant cognitive and behavioral deficits‚ highlighting their importance in overall brain function․

How Lobes Work Together

Brain lobes rarely function in isolation; instead‚ they collaborate in complex‚ integrated processes․ For example‚ recognizing a familiar face involves the occipital lobe processing visual input‚ the temporal lobe retrieving associated memories‚ and the frontal lobe confirming identity․

Similarly‚ planning a motor action requires the frontal lobe initiating the sequence‚ the parietal lobe providing spatial awareness‚ and the temporal lobe recalling relevant past experiences․

This interconnectedness demonstrates that cognitive functions aren’t localized to single lobes but emerge from distributed networks․ Effective functioning relies on seamless communication and coordination between these regions‚ showcasing the brain’s remarkable efficiency․

Clinical Implications & Disorders

Lobe damage can yield specific deficits; frontal lobe injury impacts executive function‚ while temporal lobe damage disrupts memory and language comprehension․

Neurological disorders often selectively affect particular lobes‚ highlighting their specialized roles․

Effects of Lobe Damage

Damage to specific brain lobes results in predictable‚ and often devastating‚ consequences․ Frontal lobe injuries frequently manifest as alterations in personality‚ impaired decision-making abilities‚ and difficulties with motor control․ Individuals may exhibit impulsivity‚ reduced problem-solving skills‚ and challenges initiating or planning actions․

Parietal lobe damage can disrupt sensory perception‚ leading to difficulties with touch‚ temperature‚ and pain recognition․ Spatial awareness is often compromised‚ resulting in disorientation and navigational challenges․ Furthermore‚ numerical processing abilities can be significantly impaired․

Temporal lobe lesions commonly affect memory formation and language comprehension․ Patients may experience amnesia‚ difficulty understanding spoken or written language‚ and problems recognizing objects or faces․ Occipital lobe damage primarily impacts visual processing‚ potentially causing blindness‚ visual distortions‚ or difficulty recognizing colors and motion․

Neurological Disorders Affecting Specific Lobes

Several neurological disorders selectively impact specific brain lobes․ Frontotemporal dementia primarily affects the frontal and temporal lobes‚ causing behavioral changes and language difficulties․ Stroke‚ depending on its location‚ can damage any lobe‚ leading to a wide range of deficits‚ including motor impairments‚ sensory loss‚ or cognitive dysfunction․

Alzheimer’s disease initially impacts the temporal lobe‚ disrupting memory formation‚ but eventually spreads to other areas․ Parietal lobe damage is often seen in conditions like Gerstmann syndrome‚ causing difficulties with writing‚ calculation‚ and spatial orientation․

Occipital lobe disorders‚ such as cortical blindness‚ result from damage to the visual cortex․ Understanding these lobe-specific vulnerabilities is crucial for accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment strategies․